Arkhangai to Khövsgöl Aimag, Mongolia

July 2016

I’m leaving central Mongolia for the far north. It’s a couple of days bouncing on the now more than familiar hummocky tracks that serve as roads here. Along the way I transfer to another van, this time a Soviet era all terrain beast that’s got less butt pounding but more airborne action.

We pass a horse race in the middle of nowhere, part of the annual nationwide Naadam Festival. Kids line up on full sized horses and take off across the grassy moutainsides, surrounded by more horses and motorbikes, and disappear over the next hill.

The landscape is empty here, even for Mongolian standards. Towards the end of the day, we pull up to a random nomadic family, the driver asks if there’s space to stay in their tent. Discussions are had, I’m guessing a price is suggested, driver looks disinterested and begins to drive 50 metres then pretends to make a phone call (the chances of cell coverage in these parts is nil). The owner arrives at the window, the process repeats again, this time we drive only 20 metres. Eventually they send the young daughter out with an acceptable price and it’s all on.

The traditional greetings come out, offerings of horse milk tea, dried yoghurt and snuff. Outside there’s a glorious sunset throwing long shadows across the wide valley.

Inside, the TV comes on. They use small solar panels to charge a car battery into which they plug a satellite receiver and small computer monitor. It’s a set-up duplicated in tents across the steppes. We’re entertained with some Mongolian historical movie to do with a wrestling competition and the hero trying to win the most beautiful girl in town by winning the tournament. Quality action.

Breakfast time and we’re given a clear liquid which turns out to be vodka made from fermented horse milk then distilled over the fire place. Apparently finishing your glass means you want more. It took me a few to work that out. Turns out to be a good remedy for the Mongolian roads. Breakfast of champions.

The “road” north heads through more mountainous country, over some semi alpine passes and across a huge river flowing north into Russia and the mighty Baikal. We find an old shamanistic stone totem out in a valley, draped in Buddhist prayer flags and bits of yak hair for blessings on the herd. This practice dates back millenia.

The “road” north heads through more mountainous country, over some semi alpine passes and across a huge river flowing north into Russia and the mighty Baikal. We find an old shamanistic stone totem out in a valley, draped in Buddhist prayer flags and bits of yak hair for blessings on the herd. This practice dates back millenia.

Lunch is by a distinctly aromatic soda lake that smells as if the yaks have been using it for a bath. There’s no outlet, presumably only evaporation and seepage drain this, the shore is covered in a thick crust of mineral salt, the water has that weird oily feel of super-saline lakes anywhere.

We arrive in the brightly painted and mildly amusingly named town of Moron (amusing until you find out it’s pronounced mooroon), just in time for a massive thunderstorm, stay the night and swap to another Soviet van for another 12 hour bronco session.

The landscape, nature and culture change up here. There are high mountains around, more forest which slowly morphs into Siberian Taiga carpeted by deep moss. There are less nomadic tents and more log cabins spread around, some in small clearings in the forest, others out on the grassy valleys by lazy silver rivers and lakes, thin snakes of smoke trailing above from the fires within.

The long twilight works for us, it’s almost 11pm by the time we reach our destination – a small log cabin up a mountainous valley. Inside is a single room in which the whole family sleep, a wood stove set in the middle. As always, they’re incredibly friendly and hospitable. Milk tea, home made cream cheese on fresh bread, mutton soup and fresh made yoghurt come out. Superb.

Hore trek adventure into the far north awaits the next day …

Up on top of the mountain is a shamanistic shrine where people have left offerings. There is a plague of flies in the forest here, I wonder how people live with it without going insane as I feel myself rapidly approaching that point with them in only a couple of short hours.

Up on top of the mountain is a shamanistic shrine where people have left offerings. There is a plague of flies in the forest here, I wonder how people live with it without going insane as I feel myself rapidly approaching that point with them in only a couple of short hours.

The goal was to reach the nearby waterfalls, the largest in Mongolia. Not huge by any normal standard but still impressive. Also very popular with Mongolians apparently as well. The water, fortunately full from recent summer rains (it only flows for a few weeks each year) plummets off the edge of a lava flow into a chasm below. Safety standards here are a little more relaxed as people either jump to the small island above the falls with their kids in tow, and clamber down the sheer cliff single handed (the other hand carrying children too small to walk). I see parents waving their small children over the waterfall, considered good luck seemingly – presumably for those that are successfully retrieved to relative safety.

The goal was to reach the nearby waterfalls, the largest in Mongolia. Not huge by any normal standard but still impressive. Also very popular with Mongolians apparently as well. The water, fortunately full from recent summer rains (it only flows for a few weeks each year) plummets off the edge of a lava flow into a chasm below. Safety standards here are a little more relaxed as people either jump to the small island above the falls with their kids in tow, and clamber down the sheer cliff single handed (the other hand carrying children too small to walk). I see parents waving their small children over the waterfall, considered good luck seemingly – presumably for those that are successfully retrieved to relative safety.

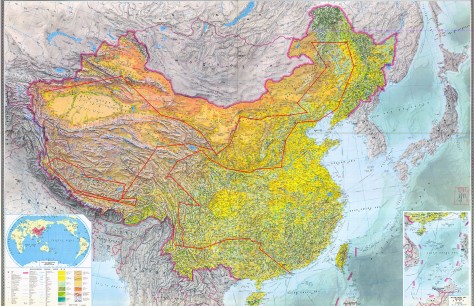

I’ve arrived from Kashgar in Beijing which is a jolt to the system. It’s been 24 years since my last visit. The waves of bicycles have gone, replaced by horn blaring traffic, but it’s not the congested smog-infested megalopolis I’d braced myself for. Don’t believe everything you read in the news. Sure it’s grown vastly over that time, but somehow it has a small city feel to it still. To Beijing’s infinite benefit, the metro system runs everywhere, is dirt cheap and runs like clockwork – if they could just do away with the airport bag scanners at every station it would be near perfect.

I’ve arrived from Kashgar in Beijing which is a jolt to the system. It’s been 24 years since my last visit. The waves of bicycles have gone, replaced by horn blaring traffic, but it’s not the congested smog-infested megalopolis I’d braced myself for. Don’t believe everything you read in the news. Sure it’s grown vastly over that time, but somehow it has a small city feel to it still. To Beijing’s infinite benefit, the metro system runs everywhere, is dirt cheap and runs like clockwork – if they could just do away with the airport bag scanners at every station it would be near perfect.

We move out to Yanguang Pass, an old garrison and lookout post (looking out over some of the most unforgiving and relentless desert stretching out into the horizon … leaves me wondering who was insane enough to be riding out across that), and guarding a nearby strategic oasis. There’s still the remains of an old sentry building on top of the hill nearby with commanding views across the sea of rocky sand spreading beyond the eye’s reach. There’s the option of an electric cart to whick you up to the top and back, I opt to just walk up which the other tourists take to mean I’m verging on insane. I want to ge an appreciation for the conditions people endured out here or something … or maybe I just don’t like being herded into sardine can compression under blaring speakers. One of the two.

We move out to Yanguang Pass, an old garrison and lookout post (looking out over some of the most unforgiving and relentless desert stretching out into the horizon … leaves me wondering who was insane enough to be riding out across that), and guarding a nearby strategic oasis. There’s still the remains of an old sentry building on top of the hill nearby with commanding views across the sea of rocky sand spreading beyond the eye’s reach. There’s the option of an electric cart to whick you up to the top and back, I opt to just walk up which the other tourists take to mean I’m verging on insane. I want to ge an appreciation for the conditions people endured out here or something … or maybe I just don’t like being herded into sardine can compression under blaring speakers. One of the two.

First lesson in not romaticising historic places in China: a bullet train brought me into town at a leisurely 200kmh where I could hop straight into a taxi to whisk me off to the Great Wall and fort where several thousand Chinese tourists had had the same intentions, arriving by the busload with flag waving tour guides and loud-hailers. It’s possible there were more selfie-sticks in operation than there were guards in the Ming Imperial Army. The fort is completely rebuilt, as is the “last stretch of Wall”, the only remnants of the original in view stretched away from the fort towards the mountains, where it’s been bisected by high speed rail links and motorways.

First lesson in not romaticising historic places in China: a bullet train brought me into town at a leisurely 200kmh where I could hop straight into a taxi to whisk me off to the Great Wall and fort where several thousand Chinese tourists had had the same intentions, arriving by the busload with flag waving tour guides and loud-hailers. It’s possible there were more selfie-sticks in operation than there were guards in the Ming Imperial Army. The fort is completely rebuilt, as is the “last stretch of Wall”, the only remnants of the original in view stretched away from the fort towards the mountains, where it’s been bisected by high speed rail links and motorways.

Mati Si was worth every effort to reach however. Tucked up on the edge of some very large mountains that form a first barrier to the Tibetan Plateau to the south sits a lush valley with an array of ancient Bhuddist temples carved into the sandstone cliffs starting from over 1,600 years ago with many of the temples accessible only by climbing hidden staircases and vertical shafts in the cliffs.

Mati Si was worth every effort to reach however. Tucked up on the edge of some very large mountains that form a first barrier to the Tibetan Plateau to the south sits a lush valley with an array of ancient Bhuddist temples carved into the sandstone cliffs starting from over 1,600 years ago with many of the temples accessible only by climbing hidden staircases and vertical shafts in the cliffs. The people are descended from a mix of Tibetan and Mongol herders, you immediately feel that surrounded by Tibetan prayer flags and stupas on the hills. It’s a blissful world away from the melee of the city to the north. People are relaxed, friendly and seem to have all the time in the world. Life moves at a very leisurely pace up here. And the air is clean and the sky blue – you learn not to take that for granted in China, especially further east where a brown soup sits over much of the country for weeks on end.

The people are descended from a mix of Tibetan and Mongol herders, you immediately feel that surrounded by Tibetan prayer flags and stupas on the hills. It’s a blissful world away from the melee of the city to the north. People are relaxed, friendly and seem to have all the time in the world. Life moves at a very leisurely pace up here. And the air is clean and the sky blue – you learn not to take that for granted in China, especially further east where a brown soup sits over much of the country for weeks on end.

In the morning I go for more hikes across the tops with more friendly locals and visit the 1,000 Bhudda caves further down the valley where a man oddly attempts to flog me plumbing fixtures. Just what I needed.

In the morning I go for more hikes across the tops with more friendly locals and visit the 1,000 Bhudda caves further down the valley where a man oddly attempts to flog me plumbing fixtures. Just what I needed.